By Steven Bishop

I am getting better at answering the question, “What you are talking about is important, but what does that have to do with technology?” This question is probably more implied, and probably more personal and internal, than one I am asked by others directly. My job title is Online Learning Designer, a role that involves:

- supporting faculty with their use of the college’s Learning Management System (LMS)

- collaborating with educational and informational technology staff to ensure currency and quality of online learning environments

- instructing faculty in the design and production of online learning objects

- providing “exceptional client-centered service on a consistent basis to all stakeholder groups”

Depending on what one thinks technology means, there is lots of room for interpretation of the above functions. Because the environment is technological (e.g. digital, computer-based, online), there can be an assumption that the primary work is within prescribed technologies. Ursula Franklin, defines a prescriptive technology as that which “Each step is carried out by a separate worker, or group of workers, who need to be familiar only with the skills of performing that one step. This is what is normally meant by division of labour.” (Franklin, 1990)

Franklin also identifies holistic technology as “…associated with the notion of craft” and involving decisions that can only be made while the work is in process, by the artisan themselves. Holistic technology is endangered in our modern, compliance-based, and prescriptive technological environment, where one misplaced character in a line of code causes failure, and where algorithms decide what information we are fed on our smart phones and computers.

There are a number of reasons why I think a holistic approach to Educational Technology is needed, and why, as a learning designer, it is my responsibility to keep this in mind when working with faculty, staff, and other educators in the development and provision of worthwhile learning environments and experiences. Some of these reasons are outlined in a presentation I developed for the Fall 2017 Educational Technology Users Group. The main points in “Practical Ethics for Educational Technology Users” are briefly discussed here:

Intersections

Educational technology exists somewhere in the intersection between human aspirations, the ways we go about doing things and “market sensibilities”. Human aspirations include intellectual, bodily and emotional sustenance, the need to learn and grow, and the need to survive and attain comfort in the world. Technology involves the means by which we meet these aspirations, and as the Greek root word techne informs, how we create, produce and manifest our aspirations. Market sensibilities include protective considerations, for example paywall barriers, compliance with Freedom of Information and Privacy Protection laws, and industrial considerations, for example efficiency and profit.

We are educational technology users, and we make practical decisions every day. We probably don’t think, in education, that we are faced with making life-or-death choices involving other people, as is brought to our attention when posing the well-known trolley problem, where the choice is between doing nothing (which results in 5 people dying) or choosing to pull a switch (which results in ones own action directly related to one persons death). What we can consider, is the interrelationship of ethics and technology. Choices that designers and instructors make impact learners’ educational experiences, and by extension their lives, for better or worse.

When thinking about educational technology, I find it helpful to remember the original and retentive meanings of the word education:

- the drawing out of that which is within

- bringing the hidden to light

- rendering the potential actual

- facilitating the process of growth

All of these meanings indicate a human and nurturing process. We who are in the education sector, if we are dedicated to education, whatever our job title, are educators. Staff, faculty and administrators. Otherwise, who can claim to be an educator?

I also find it helpful to remember the meanings of the word technology. Technology is the intersection of art, craft and logic. “…Techne and the knowledge of making things…emancipated humankind from the mythical past and steered a path towards intellectual advancement.” (Garner, 2013) Ursula Franklin, in her 1989 series of Massey Lectures on The Real World of Technology, defines two meanings: holistic, in which the skilled crafts-person could make almost every tool needed, and had much creative control over the entire process, and prescriptive, in which the control is shifted to a hierarchy of managers, and the human is part of a larger machinery. It is the latter meaning of technology that we probably most often encounter, and in my estimation, one that needs to be balanced with the holistic meaning.

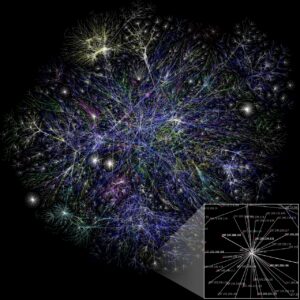

Our current educational technology is part of a series of revolutions. This image, from the Opte Project which produces visual snapshots of the internet, provides a sense of the interconnectedness that has the potential to both benefit and betray us, depending on our collective choices. Take a moment to reflect on how similar this image is to images of the galaxies, and to images of neural activity in our own nervous systems. Are we using technology to project our understanding of the cosmos and of our own microcosm onto the physical world?

We make collective choices, and technological practice involves a common way of doing things, and places parameters around individual choices. Practice means, “The way we do things around here”. How do we do things around here? Are the tools and protocols we follow, promote, and encourage students to use holistic or prescriptive? Do they support creative and critical thinking, whole-person development, and human dignity? Where are the places where it necessary to push back against a culture of compliance and control, the unintended consequences of division of labor and the loss of holistic skill, and the military efficiency of market technologies?

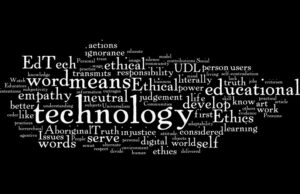

Educational technology practices, in which we are all engaged, also involve values and ethics. There is no such thing as a neutral practice. Practical ethics are always personal. Ideas such as ethical responsibility, actions, universal design, empathy, social justice, respect, humanizing environments, relationship of self to other, power imbalances, threats to freedom and other considerations are worth our attention.

Educational technology designers have influence over users, and users signal their approval to designers. At the 2017 Summer Institute hosted by the Digital Pedagogy Lab, a workshop inquiring into how an EdTech tool could be used to change the world was conducted. We asked, “Are the tools we are working with, and encouraging students and others to work with, world-changing tools?” The architect William McDonough states that “Design is the first signal of intent” (McDonough, 2017). Creating things cannot be separated from the intentions and values of their creators. There is no such thing as a neutral educational technology.

Everything begins with self-awareness. Paulo Freire’s term conscientization implies the raising of consciousness, and raising an individual’s development from magical to naïve to critical social consciousness. (Freire Institute, 2017) The need for human ethical choices is based on self-knowledge and empathy. A team comprised of an educational academic, an instructor and two online learning designers facilitated a workshop on creating emotional safety in learning environments at Douglas College recently. Much of the work we did on that day had to do with self-awareness of our own fears, perceptions of self, and threats to one’s sense of self. This is important, ethical, requisite work.

Nobody wants to get involved with this guy. And this is what we are worried about – robots taking our jobs, AI revising the rules. We don’t have to worry about robots from the future coming to exterminate us, we have to do something about the contemporary robots commanding our attention, mining our personal interests and activities, and our own tendency to (in the words of Neil Postman) “amuse ourselves to death”. (Postman, 1985). We have to make decisions about how we respect our own and others’ attention.

The Terminator has guns to kill the body, bots have algorithms to kill our attention…

Since meeting Audrey Watters in 2016 at the ETUG conference, I’ve reflected on her call to “be less pigeon” (referencing BF Skinner’s controversial experiments with pigeons and people). The pigeon metaphor also works with a story I am familiar with. An aged spiritual master has to decide who is worthy of his two foremost disciples to carry on the work. Who has understood the teachings? The disciples are each given a pigeon with instructions to kill it where no one can see.

One disciple returns immediately with the dead pigeon, the other returns after some time with the live pigeon, and reports “at first, the pigeon was watching me, and then I was watching myself.” This is the kind of self-awareness needed to develop practical ethics.

Empathy is another good starting place. What was the experience of people in our learning environments before we met them? India, China, African high school (where do our instructors and students come from?) Children of Residential school survivors? This picture is was provided by a current student and staff member when I asked him what his high school was like. Note the amount of paper, the close proximity of seating, and the absence of electronic technology. There’s nothing wrong with this classroom of course, it’s just very different from what the student might experience in one of our institutions.

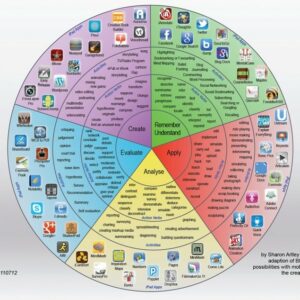

Critical evaluation of educational technology tools is another good starting point. You’ve probably seen charts like this one pairing Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning verbs with a plethora of Silicon Valley apps. At the Digital Pedagogy Lab, Social Justice Stream, we examined digital tools based on what the tool does, its pros and cons, who owns it, and whether it supports open and just practices.

We’ve all got to pull together, and we need integrity in order to do that. Integrity is another name for personal, practical ethics. We all have to pull together to better the world. We can’t wait for the institution to mandate integrity, we each have to manifest it in our own practice. An institution’s integrity is based on the collective practice of its members.

The practically ethical are also called upon to resist injustice. This socially-conscious librarian is tossing Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaiden’s Tale at sexist elites. What kinds of things could be considered for a personal, practical ethics?

Here’s a partial list of things to resist:

- Disrespecting others

- One’s own personal and inherited cultural biases

- Blaming others (e.g. the younger generation, the older generation, senior management, the government, the liberals, the conservatives…)

- Categorizing people (e.g. persistent myth of learning styles)

- Reinforcing silos, filter bubbles, echo chambers

- Distraction and diffusion of one’s own attention

We have the ability to communicate embedded deep in our DNA. Holistic educational technology implies dialogue. Consider this thought from James Blackburn, discussing the Freire’s thoughts regarding the role of the educator in dialogical education:

“The educator, rather than deposit ‘superior knowledge’ to be passively digested, memorized, and repeated, must engage in a ‘genuine dialogue’, or ‘creative exchange’, with the participants… Freire’s concept of dialogue requires a lot of the educator, however. It must be ‘authentic’, ‘creative’, and can only take place with ‘sympathy and love’…In short, it requires a fundamental ‘revolution in thinking’, as the educator must shed ingrained attitudes of ‘anti-dialogue’ which may have become automatic.” (Blackburn, 2000)

I have witnessed this principle in action. A workshop participant gave the most graceful, patient and understanding response to a privileged and well-meaning but inaccurate point of view, instead of shooting it down. I believe everyone benefits from this approach.

People, ourselves and others, have immeasurable depth. No one can be described exactly as they are.

And the most salient quality we possess is our attention. When we design, select, use, and prescribe technology, let us also remember to respect attention: one’s own and others.

We know these things from our earliest age: treat others as you would like to be treated, share with others, help others who need help. Respect our own attention, and respect others’ attention. The Golden rule. But what does it have to do with technology? Perhaps a better question might be, what does technology have to do with actualizing my life, and the lives of students? If we are talking about a balance between holistic and prescriptive technology, perhaps it has a great deal to do with the human considerations touched on here.

Leave a Reply